In April 2022 I finally took the leap and decided not to renew my teaching contract. Instead, I chose to apply for a place on a one year course to study Japanese carpentry and house building.

The course was a one year residential architecture course (住宅建築 -‘jutaku kenchiku’), based at Takumi International Academy in Minokamo City, Gifu Prefecture.

https://www.takumi.ac.jp/index.html

Essentially the course is designed for high school graduates (18 years old), who are looking for practical training and career guidance to help them find work as quickly as possible. There is no age limit for applicants, which came as a relief to me!

The application process involved writing a statement as to why you wished to study there. There was also an aptitude test and an interview.

The aptitude test was similar to the 11+ (if you’re from the UK you might know what I am talking about). It was a booklet with pattern recognition tasks, number sequences and other logic / motor skills tasks to be completed within a set time limit. (If you search IQ / aptitude tests online you will see some examples of the kind of tasks).

I managed to pass the entrance requirements and was offered a place. I was also offered a room in the dormitory from Monday to Friday. (You had to vacate the room and return home on weekends).

Course Structure

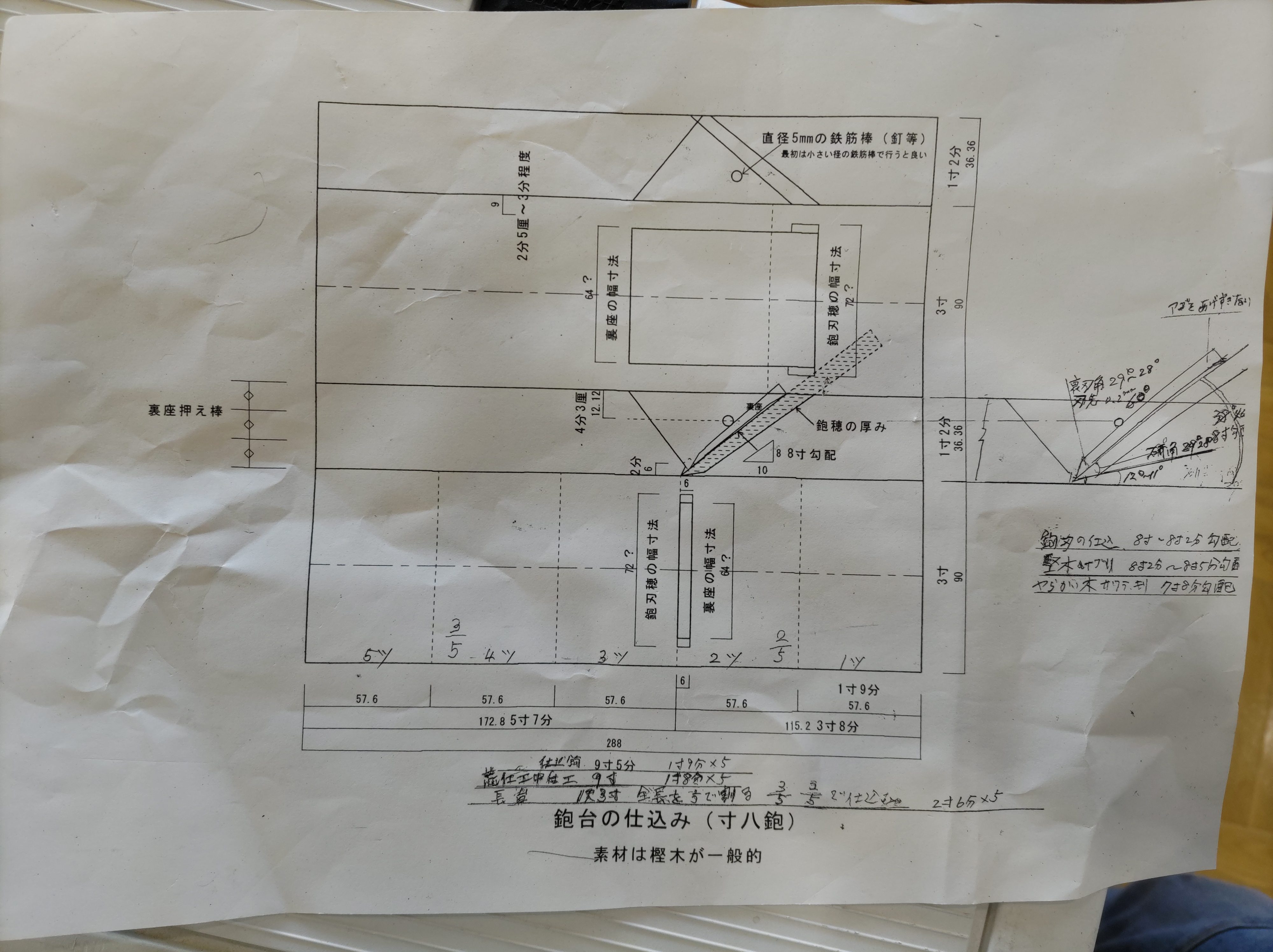

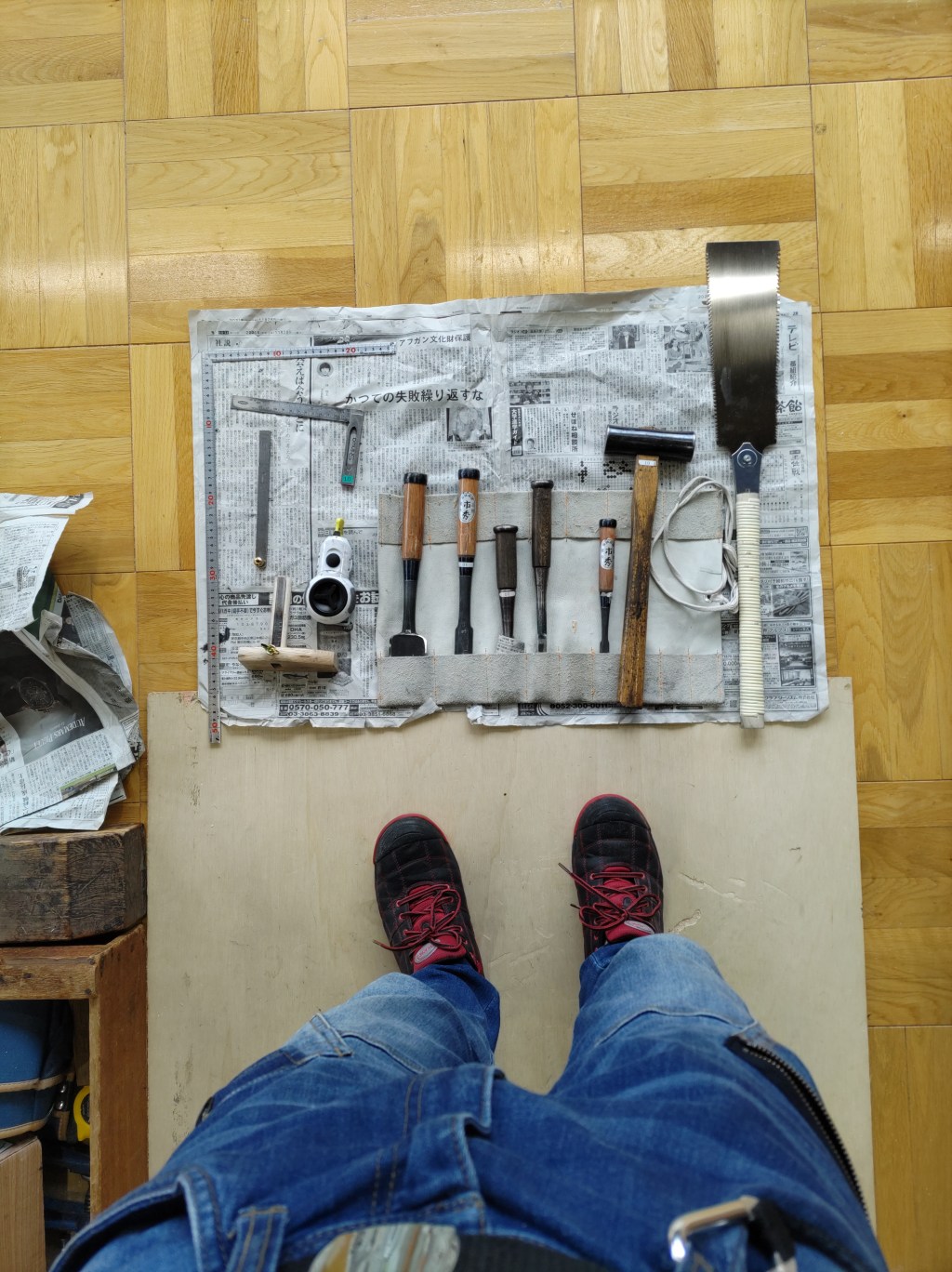

The course was split roughly 50/50 into theory sessions in the classroom and practical training sessions in the training ground (自主場 – “jisshyu ba”).

We spent the majority of our practical training building a small house, which was constructed inside the training ground – this meant that work could continue throughout the year and the schedule wouldn’t be affected by the rainy season or the brutal heat of mid summer.

As the building work progressed, professional trades people and companied would come and provide specific training during different stages of the build:

- Plastering – both using plasterboard and traditional bamboo lattice (竹小舞 – “takekomai”)

- Roofing – Using traditional Japanese roof tiles (瓦 – “kawara”). This also included trying the national roof tiling skills test.

- Metal siding – A two day course which involved cutting and installing sheet metal siding (板金 – “bankin”) on the external walls of the house.

- 2D design / CAD – These classes were taught by a qualified architect. The focus was on learning how to use JW CAD (A free Japanese 2D CAD software).

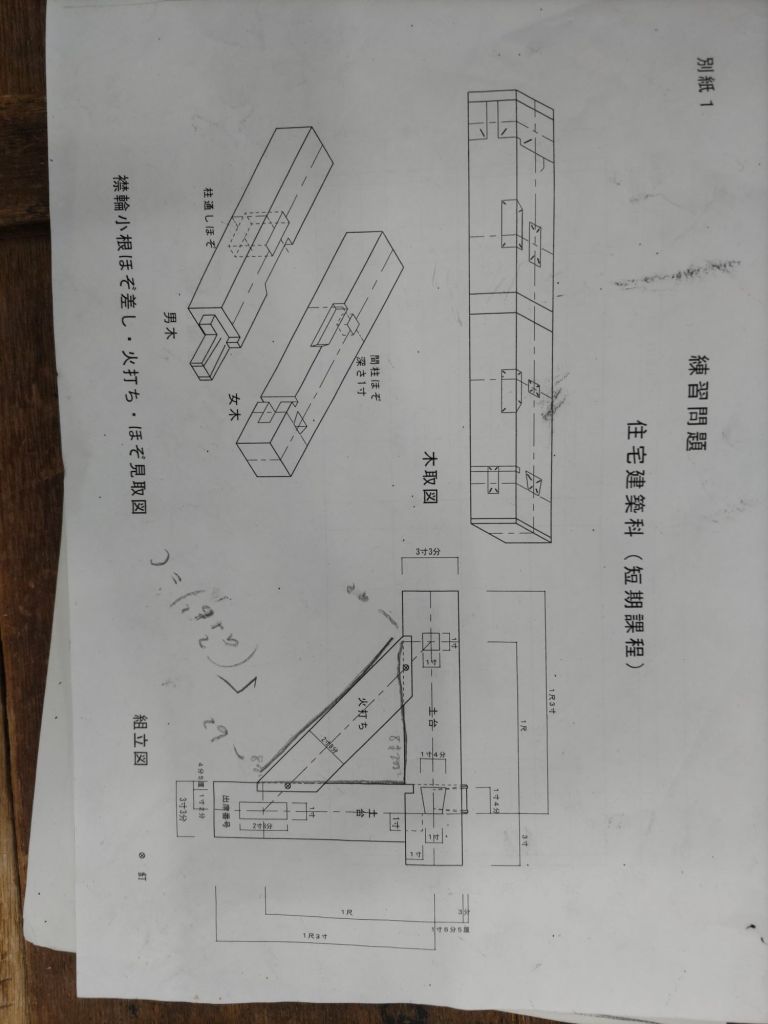

The course finished with a practical exam, which involved making a corner section of a mud sill with a brace under timed conditions. After the exam finished, the pieces you make are taken apart and measured / tested for tolerances.

I really enjoyed the opportunity to try different trades and learn directly from craftspeople who have years of experience. I would also add that its a unique opportunity to practice speaking Japanese in the context of a construction site without the pressure of working for a real client / company, who may not be so forgiving about mistakes or delays whilst you are learning.

One of the areas I struggled with was living on the campus from Monday to Friday. I knew that immersing myself in Japanese was key to making the most of my one year experience, however I underestimated the challenges of living alongside 18 year old Japanese guys who have never lived away from home before. Add to this the fact that it was during the corona pandemic, so in addition to a 9 o’clock curfew, there were many other rules and schedules in place to try to mitigate infection.

Cost of study

As a final note, I will mention finances. I worked for several years in Japan before I decided to study at the academy. During my previous employment I made contributions to employment insurance (雇用保険 – koyō hoken), which I was able to use to subsidise my studies. I believe the course itself is also heavily subsidised by the prefectural government, meaning even without financial help, it is incredibly affordable. Unfortunately I didn’t keep detailed records of what I spent during the year, but if you check the academy’s website I am sure the current costs will be listed.

Overall, I would recommend the experience to anyone looking to immerse themselves in Japanese and to gain industry specific knowledge without investing a vast amount of time and money. There are other courses available which cost more money and take 2 or 3 years to complete, however I think this particular course is a fantastic opportunity for anyone who wants to take their first steps into the construction / craft industry, especially if you are unsure of the specific path you want to follow.